At the 2022 7Gen Investing Summit, I enjoyed spending time with team members from Siċaƞġu Co, a Foundation grantee I work closely with. Photo courtesy Siċaƞġu Co.

Reciprocal relationships are grounded in and affirm our humanity, hearts, spirits, and interdependence. They are forged over time, with deep intentionality and care.

In each conversation, I’m challenging myself to share from my heart, listen deeply, reflect back what I’m learning, and think more intentionally about my responsibilities.

Fishing boats, many financed by Lummi CDFI and owned by tribal fishermen in the Pacific Northwest, stand ready to haul in crabs, halibut, prawns, and salmon. Photo courtesy Lummi CDFI.

How different things would be if we put values and collective care at the center of everything we do.

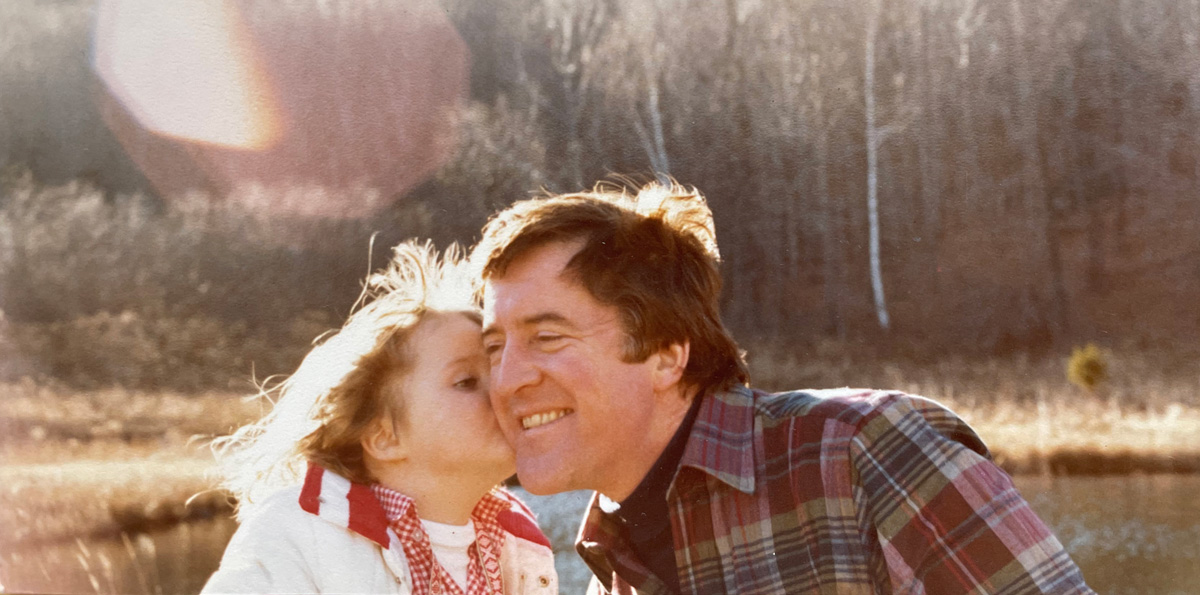

I hope to carry on the values my father taught me—foremost among them, love.

We have moved away from an economic frame toward a grantmaking approach focused on advancing justice so that communities can thrive on their own terms. This approach is more holistic and honors the different histories, cultures, worldviews, and values of the people we serve.

Photo top: Canoes are ceremonially reawakened during the 2022 Gathering of the Eagles Canoe Encampment on Lummi Nation territory in the Pacific Northwest. Photo courtesy Lummi CDFI.