Our board members not only share our commitment to racial equity, they also bring lived and professional experience.

We were planning to hold our annual board learning retreat 150 miles northeast of the Twin Cities in the Lake Superior port city of Duluth, MN, in May 2020. Unfortunately, the global pandemic canceled our plans, and we met on Zoom instead.

If we had made it to Duluth, our visit would’ve occurred just weeks in advance of an infamous racial injustice milestone: the centenary of one of Minnesota’s most notorious lynchings.

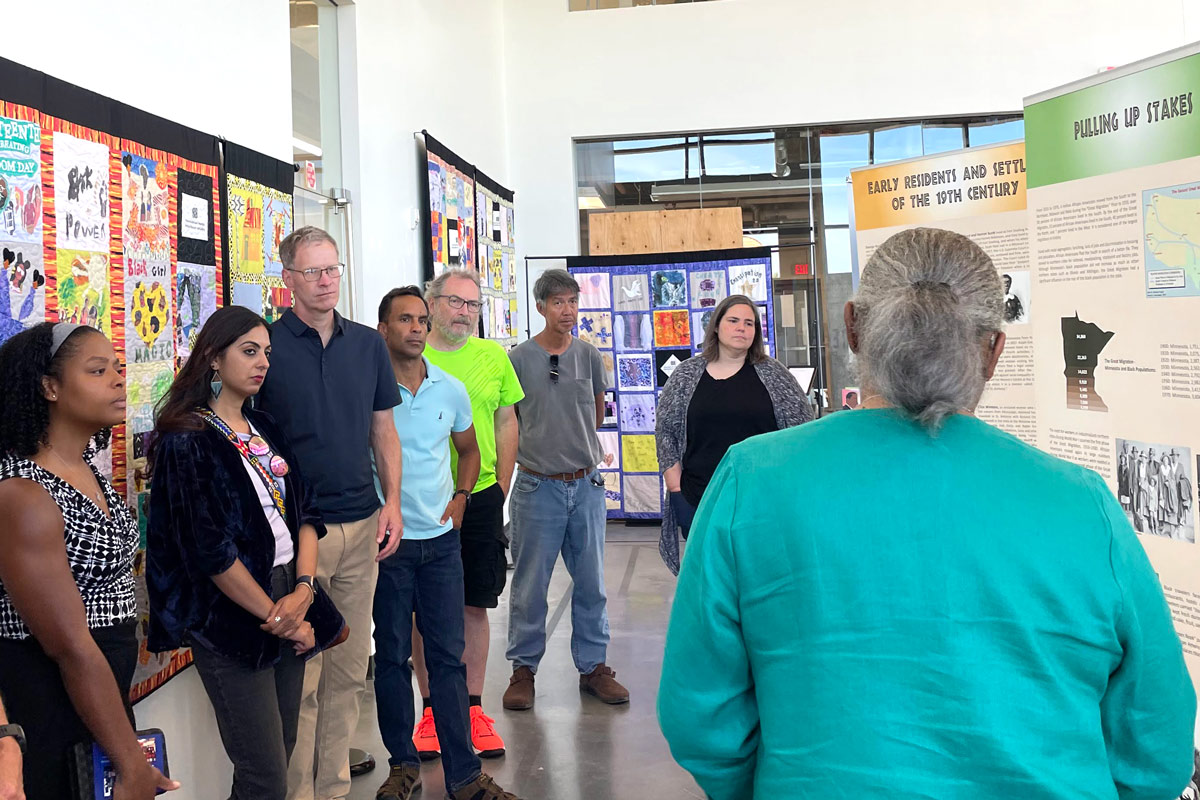

Dr. Duane Carter discusses Duluth and race with me.

I want to share with you my conversation with our board member Dr. Duane Carter about his experience growing up Black in Duluth during the 60s and 70s and how this shaped his views on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). As a foundation CEO who grew up with plenty of white privilege in the New York City suburbs, I have a lot to learn about race and equity from Duane.

He recently retired from a distinguished career at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, where he most recently was a senior vice president.

KW: Duane, June 15, 2020, marked the 100th anniversary of the lynching of three Black circus workers—wrongfully accused of a crime—in downtown Duluth. There are obvious connections to the killing of George Floyd. What are the observations that come to mind to you, having grown up in Duluth and having made Minneapolis your current and longtime home?

DC: Yes, on June 15 this year, a “Day of Remembrance” was held at the Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial, which stands at the same downtown intersection of East First Street and North Second Avenue East in Duluth. Organizers were aiming to fill the streets with 10,000 people on that day, which some believe matches the size of the crowd in 1920. Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative and author of New York Times bestseller Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, was scheduled to give a keynote speech. Although the event was postponed due to the pandemic, it’s a very important anniversary.

KW: Did anyone from your family witness the event?

DC: No, we came to Minnesota later, in the 1950s.

I was a military brat. My father was in the United States Air Force, and one of his assignments required a move to Duluth in the late 1950s. My father was from Philadelphia and my mother was from the Shreveport, LA. Early on, my mother cried every day because the weather was so bitterly cold.

KW: I imagine it must have been pretty cold in more ways than one . . .

DC: Well, yes and no.

We felt welcome on the military base because there were families and people like us. We spent most of our time on the base. My mother shopped for food and household items at the commissary. Our doctor and dentist visits were on the base, as well as our leisurely entertainment (kiddie bingo, movies, and dances). My parents played cards and socialized with other military people.

In my early teens, I actually became a better basketball player by playing against the airmen on the base, who came from all over the United States. We felt comfortable and like we belonged. However, the broader Duluth community was not as inviting, which was similar to other places in the country during that time period.

KW: How did this sense of exclusion show up in your day-to-day lives?

DC: Initially, people would not rent to our family. My parents drove all over the city to find somewhere to live. Eventually an older Black woman, who owned a duplex house, rented the upstairs section to our family. A few years later, my parents bought a house in a residential neighborhood.

Although we knew our neighbors, we did not have the same social connections as we did in the Air Force community. In the 1960s and 70s, the population in Duluth was around 100,000 people, with people of color representing less than half a percent.

The largest population of people of color were Black and Native American. As a result, these two communities had a strong bond within their own communities. Anytime we saw other Black people, whether we knew them or not, we waved to them to show our appreciation and excitement that there was another Black family in Duluth.

“Anytime we saw other Black people, whether we knew them or not, we waved to them to show our appreciation and excitement that there was another Black family in Duluth.”

Dr. Duane Carter

KW: How do those memories compare to the Duluth you encounter when you go back home in 2020?

DC: Things have changed in a number of ways. The Air Force base closed in the early 1980s. Today, the population in Duluth has declined to around 85,000, with Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities representing slightly more than 10 percent. The largest of these populations are those who identify as two or more races.

These changing demographics have helped to make people feel more welcome. In 2019, Duluth elected its first Black person to the City Council. She was born and raised in West Duluth, and I know her and her family very well. So there has been progress on diversity and inclusion, and maybe even some progress toward racial equity.

But much more is needed for BIPOC communities to feel a sense of belonging in the broader community.

KW: I’m guessing that growing up in that environment—in one of the relatively few Black families in a place where your sense of belonging was iffy at best—shaped you in lots of ways. And I know you well enough to know that you’ve led an extremely successful life. How are those two things connected—your Duluth childhood and your success as an adult?

DC: Growing up in Duluth provided good training and preparation for navigating corporate America and my career in the financial services industry. In 2005, I became the first Black senior vice president and member of the executive leadership team of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, which was a rare kind of feat for the Federal Reserve System and the financial services industry, as a whole.

This was not lost on me.

I was often the only person of color in meetings and at events and social gatherings, which was the story of my upbringing in Duluth. The way I spoke and my mannerisms opened doors to opportunities that I could have never imagined as a child. The ability to interact and relate to people of different races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic status was very easy and natural for me. This is because of the lived experience in Duluth.

I wouldn’t pick anywhere else to grow up because I learned a lot. In Duluth, we didn’t have a lot of diversity, but it forced you to appreciate the diversity you did have.

Furthermore, I can sense when an individual is comfortable or uncomfortable being around people who are different than he or she is racially, intellectually, and socioeconomically, as well as that person’s genuineness in advancing DEI.

“The ability to interact and relate to people of different races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic status was very easy and natural for me. This is because of the lived experience in Duluth.”

KW: And, you’ve mentioned how DEI won’t advance without a willingness to be uncomfortable and intentional?

DC: I believe that real learning is pushing you out of your comfort zone and being intentional with your actions. I never learned anything or made any progress being just comfortable. And so, when I think about how we approach equity and the crises of today, we spend a lot of time trying to make people feel comfortable. But this will not move us forward.

“Real learning is pushing you out of your comfort

zone. . . . When I think about how we approach equity and the crises of today, we spend a lot of time trying to make people feel comfortable. But this will not move us forward.”

KW: What’s an example that comes to mind?

DC: A CEO for a top 10 bank recently said the reason the bank hadn’t met its diversity and inclusion goals was because there wasn’t enough qualified BIPOC talent. That’s been the same line I’ve heard throughout my whole career.

We shouldn’t give someone a free pass on this. Many BIPOC students went to the same schools, took the same classes, and earned the same degrees as he did. So, it’s not a question of whether enough qualified talent exists, but whether he’s willing to hire them.

Women and people from BIPOC communities are hired on account of experience, but white males are hired because of their mere potential. We have to start thinking of the potential of all people. It exists. The reason they’re not being hired is that people like this CEO and his executive team aren’t looking for the opportunity or spending time finding reasons not to hire them because it’s uncomfortable.

If we think about candidate slates and think of success being that we have a diverse candidate slate, we’re never going to get to the point where we’re starting to hire. Instead, we need to measure success based on the candidates we actually hire, not people who were interviewed.

The reason there’s no progress is because there’s no accountability. No one wants to be accountable because when you’re accountable you have to have good outcomes, and there are consequences for poor performance. Similarly, there are clear consequences for CEOs and executives who do not meet their budget, ROI, and earnings-per-share targets. This should be the same for an organization’s efforts as it relates to DEI.

“Women and people from BIPOC communities are hired on account of experience, but white males are hired because of their mere potential. We have to start thinking of the potential of all people. It exists.”

KW: As a board member, a former community banker, and a longtime executive at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, what are some of the ways that you’ve experienced racial equity, having spent most of your life in Minnesota?

DC: I spent most of my career with an enormous weight of responsibility for being the first or the only BIPOC person in the room. I was concerned that others might use me as the reason for not including BIPOC people in the future. So I had to be overly prepared for each meeting and topic and be able to talk about these issues. But, my approach changed over time.

What I found early in my career is that I wanted you to know I was in the room. Whatever meeting I was in, I was going to weigh in and I was going to demonstrate my intellectual ability. I wanted you to know I was confident, comfortable, and as smart as everyone else in the room. And, this came from my upbringing, from my father.

He always talked about being proud. You have to compete every single day and compete to win.

And then, later in my career, I realized that your experience, your education, and your wisdom all come together. I became comfortable enough in my own skin, and I didn’t have to let you know I was in the room. You knew it when I walked in.

I got to this place where I wanted to make a difference for others, for the next generation. I thought that if I could do something, maybe the lives of my kids and grandkids wouldn’t be as tough.

I’ve become comfortable being willing to be uncomfortable again, to make it better for someone else. This is the reason that our blog conversation is so important.

“The reason there’s no progress is because there’s no accountability. . . . There are clear consequences for CEOs and executives who do not meet their budget, ROI, and earnings-per-share targets. This should be the same for an organization’s efforts as it relates to DEI.”

KW: We’re interested in sharpening our own approach as a funder so that the importance of racial equity is more central. And, you’ve played a big role. What are you seeing for the future of the work?

DC: We need to be more intentional in our DEI efforts and initiatives. This includes investing more in BIPOC communities, people in rural areas, refugees, and immigrants, providing access to capital and resources, advocating for financial inclusion, supporting women- and minority-owned business enterprises, and influencing government policies for systems change.

I serve on the Foundation’s investment committee, and we just finished the process of applying a DEI lens to the investment portfolio. It was an intentional way of communicating to the investment industry that this is important to the Foundation. We found that the Foundation’s investment managers are more diverse than those of most foundations; we must continue to encourage these investment firms to better reflect DEI in their funds management and leadership team.

More importantly, we must also encourage other foundations and government pension program administrators to apply a DEI lens to their investment portfolios. This could go a long way in holding these investment firms accountable for DEI, which is necessary for systems change in the industry.

“We need to be more intentional in our DEI efforts and initiatives. This includes investing more in BIPOC communities . . . and influencing government policies for systems change.”

KW: I agree. And I’m grateful that you’re continuing to serve as our board’s investment committee chair. It’s a case of the right leader in the right place at the right time. Many of us are hopeful that 2020 marks a reckoning—long overdue—with the realities of racial injustice in this country. Your insights and experience are making NWAF a better organization as we rise to this opportunity. Thanks for your leadership, Duane, and thanks for your friendship.

Author

Kevin Walker

President and CEO, Northwest Area Foundation