We’re part of a community of practice on racial capitalism, which is devoted to the pursuit of alternatives.

Over the past year, the Foundation has been realigning its grantmaking approach to focus on social, racial, and economic justice. This means that everyone has real opportunity to thrive on their own terms, and the outcomes of their lives are not shaped by their race, ethnicity, social status, or economic class.

However, disparities in the region we serve keep individuals and families struggling to survive, with low-wage workers laboring in unsafe working conditions so as not to risk losing their source of income. A striking example of this played out at the Smithfield Foods plant in Sioux Falls, SD, near the beginning of the pandemic.

The plant’s workforce includes many immigrants and refugees. Relying on foreign-born workers (many of whom overstayed their visas or are undocumented) is a long-standing practice of meat processing plants that gives companies the upper hand over workers through threats of deportation. It also undermines labor organizing.

The conditions at the plant led to one of the largest outbreaks of COVID-19 in the US. South Dakota Voices for Peace (SDVFP), one of our grantees, advocated for Smithfield’s employees and helped make public how the company was treating its workers.

Examples like this have led us to search for root causes of disparities.

Because of the efforts of SDVFP and the community, Smithfield was one of the only plants in the country to shut down and enhance cleanup and mitigation efforts. SDVFP also created the state’s only fund for emergency relief for immigrant families. But too many other people deemed as “essential workers” across the nation had to keep on working without protection or support.

Examples like this have made it apparent to us that we cannot work toward social, racial, and economic justice without understanding what harm has been done to communities of color by an unjust economic system.

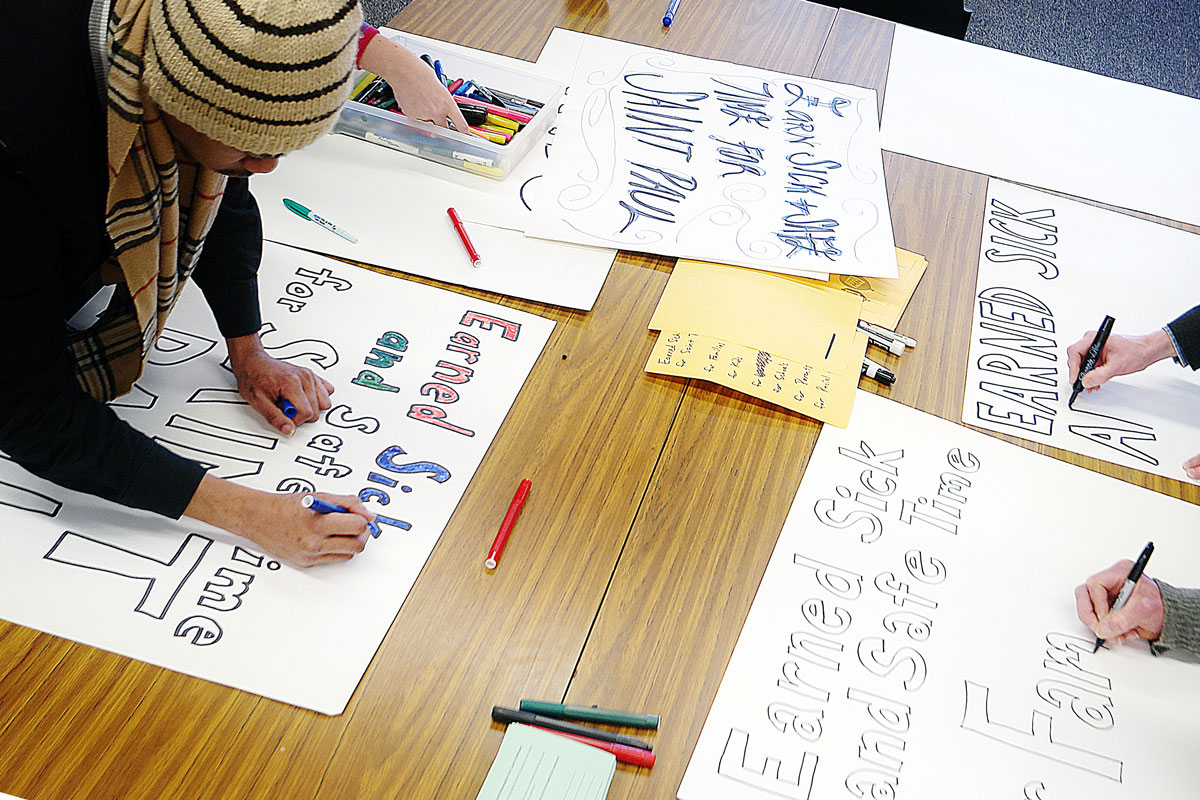

As a cohort of program officers, the three of us joined the Racial Capitalism Community of Practice in November 2021.

The community of practice was convened by Neighborhood Funders Group’s Funders for a Just Economy, in collaboration with Liberation in a Generation and others. Over eight months, the community of practice brought together staff from philanthropic organizations across the country to explore the connection between racism and capitalism and how this has intentionally produced disparities for centuries that continue today.