And that baseline goal to provide banking services to the unbanked remains critical. “We’ve learned over the years—and especially during the pandemic—that the gap in access to capital remains significantly wide, especially in rural America, tribal environments, and marginalized communities,” says Lynn Meyer, director of lending at Community LendingWorks, a Foundation grantee and CDFI focused on strengthening underbanked Oregon communities through business and personal lending.

Some CDFIs have adopted mainstream banking models that emphasize numbers and scale and avoid risk, practices that unintentionally perpetuate the systemic barriers CDFIs were designed to topple.

Nikki Foster, a Foundation program officer who works closely with many of our CDFI grantees, puts it this way: “After the racial reckoning our country has been experiencing, and fueled by the Foundation’s new grantmaking approach, we asked: Are we supporting racial equity and racial justice to the best of our capacity? Are we, even unintentionally, keeping in place barriers posed by our current banking systems? How can we improve, especially with CDFIs?”

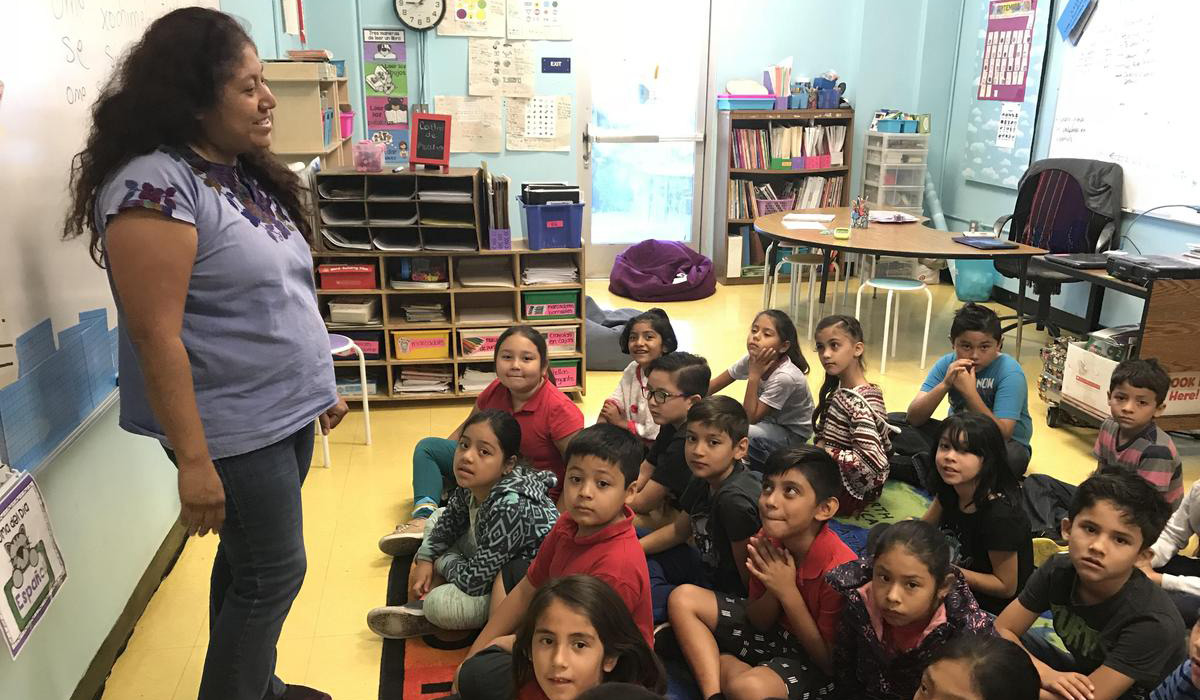

NDN Fund loan recipient, Indigenous-focused Anahuacalmecac International University Preparatory of North America, Los Angeles. Photo courtesy of NDN Fund.

Kim Pate (Cherokee and Choctaw) is managing director of NDN Fund, the impact investing and lending arm of NDN Collective, an Indigenous-led organization that builds Indigenous power. It advances narrative change, activism, grantmaking, capacity building, and other activities that help Indigenous communities make decisions about their lives and enact their decisions.

Community LendingWorks helped Amy Baker, founder of Threadbare Print House, Eugene, OR, purchase new printing equipment to expand production capacity. Photo courtesy of Community LendingWorks.

Maggie Kirby Weiland is SVP and development director of Craft3, a CDFI that serves Washington and Oregon businesses, nonprofits, tribes, and individuals. Craft3’s investments build household and business wealth, amplify community voice and agency, and create lasting networks of trust and mutual support. Maggie says she hopes impact investors will stay committed to advancing racial equity.

Craft3 customer, Soul Collective, Seattle. Photo by Carly Diaz.

“CDFIs and their funders share the same central goal: building financial equity in underserved communities. And there’s room to be more collaborative in how we structure the funding that will benefit our borrowers.”

Che Wong

Senior Business Lender – Equitable Lending Program Manager, Craft3

PHOTO TOP: Craft3 customer, Jackson’s Catfish Corner, Seattle. Photo by Carly Diaz.